There are a lot of terms thrown around when you’re learning how to make soap. The most tricky of them for a newbie to learn and recognize is ‘trace.’ All the books, blogs and videos say to stop stick blending when you’ve hit ‘trace’ and then, more confusingly, it may have been referred to as thin, medium or thick trace. What is trace? Simply put, trace is a point in the soap making process when oils and lye water have emulsified. Once the soap has reached thin trace, it will continue to thicken over time.

Mixing lye water and oils together starts the saponification process. Saponification occurs once the oil and lye molecules create new soap molecules. If you are a visual learner, this Soap Queen TV episode explains the saponification process visually. And for even more information, in Erica Pences’s online classes (here and here) she delves deep into trace and the uses of different types of trace. Once the lye and oils are saponified and the two will not separate, the soap has reached trace!

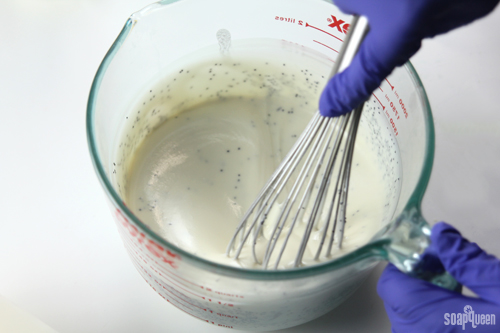

Immediately upon pouring lye water into oils, the mixture will begin to turn slightly cloudy and milky. With a few pulses and stirs of the stick blender, the entire mixture will turn a creamy consistency. This process happens fairly quickly. Before the age of stick blenders, it could take hours for soap to reach trace! In the photos below, you can see the lye water and oils are beginning to emulsify. Trace has not been achieved.

Notice the streaks of oil in the photos below? These mixtures have not reached trace, because they are not thoroughly mixed. Some of the oils have not yet started saponification, and the mixture is not completely emulsified. These mixtures need more stirring and stick blending to reach trace. If the soap was poured into the mold at this point, the soap would not properly set up. There may also be pockets of unsaponified oil and lye in your soap, which may cause skin irritation.

Notice the streaks of oil in the photos below? These mixtures have not reached trace, because they are not thoroughly mixed. Some of the oils have not yet started saponification, and the mixture is not completely emulsified. These mixtures need more stirring and stick blending to reach trace. If the soap was poured into the mold at this point, the soap would not properly set up. There may also be pockets of unsaponified oil and lye in your soap, which may cause skin irritation.

With a few more pulses and stirs with the stick blender, the soap will reach light trace. Light trace refers to soap batter with no oil streaks, and has the consistency of thin cake batter. The batter will be easy to pour, as shown below. Thin trace is an ideal time to add colorants and fragrances because the thin texture is easy to stir and blend. Light trace is perfect for swirled cold process designs, such as the Fall Sherbert Cold Process and theFrench Curl Cold Process soap. If you’d like to see light trace in action, check out the Instagram video below!

Once the soap reaches light trace, medium trace soon follows. Medium trace can be recognized by a a thick cake batter or thin pudding consistency. Trailings of soap stay on the surface of your soap mixture when lightly drizzled from a few inches overhead. Medium trace is a great time to incorporate additives that need to suspend within the soap such as poppy seeds in the Lemon Poppy Seed Cold Process Tutorial.

Adding poppy seeds into medium trace soap keeps them evenly suspended throughout the batter.

Adding poppy seeds into medium trace soap keeps them evenly suspended throughout the batter.

In order to reach thick trace, excessive stick blending is usually required. Thick trace is the consistency of thick pudding and holds its shaped when poured. Thick trace is perfect for bottom layers, as it is able to support lighter soap on top. It’s also great for creating textured tops, as seen in the Christmas Tree Swirl Cold Process. An extremely thick trace is necessary for creating cold process soap frosting, as seen in the Whipped Cold Process Frosting on Soap Queen TV.

When making cold process soap, beware of false trace. False trace occurs when soap batter appears to be a thick consistency, but the oils and butters have not saponified. Perhaps the most common cause of false trace is using solid oils or butters at too cool of a temperature. If solid butters and fats are below their melting point, the oils and butters may re-solidify. When this occurs, the soap batter may begin to thicken due to the oils and butters cooling and solidifying, and not because saponifaction is taking place. To avoid false trace, ensure any hard oils or butters are thoroughly melted and do not cool during the soaping process.

Factors that can affect trace:

- Stick blenders bring soap to trace more quickly than stirring by hand. When mixing your water and oils, alternate between stirring and pulsing the stick blender in short bursts. Once the soap has reached a thin trace, do not continue stick blending unless you’d like to reach a medium or thick trace.

- Some fragrance oils can accelerate the soap batter, causing it to reach a thick trace more quickly. To avoid this, use a whisk to blend in fragrance oils rather than a stick blender. Mixing in a fragrance oil with a stick blender can cause even the most well behaved fragrance oil to accelerate trace. Read more in the Soap Behaving Badly post.

- Adding fragrances after colorants and other additives gives you more time to work with the soap before a medium or thick trace is reached.

- Some additives, such as clay, affect trace. This is why pre-mixing with water helps to slow water absorption when using clays. The water and oil absorbing properties of the clay can speed trace.

- The oils and butters used will affect how quickly the soap will reach trace, and how quickly it will turn into medium or thick trace. Soap made with a high percentage of hard oils and butters will reach trace more quickly than soap made with mostly liquid oils. For example, the Castile Cubes Cold Process are made with 100% olive oil. With no hard oils or butters, this soap could be stick blended for a long time before reaching medium trace!

- Temperature also plays a part in trace. When soaping at higher temperatures, medium and thick trace will be reached more quickly than when soaping with cooler temperatures. If your design requires a lot of swirls, soaping at room temperature is common.

- Water discounting results in faster trace. A water discount is the process of decreasing the amount of recommended water in a recipe. Water discounting results in a harder bar of soap, with a shorter cure time. But, when water is discounted the recipe will reach medium and thick trace faster. Because of this, water discounting is recommended for more advanced soapers.

- Adding cold additives, such as cold milk or cream, at the end of your soapmaking process can dramatically speed trace.

- Increasing the superfat in a recipe will result in a slower moving recipe. Superfat is the amount of oils and butters in the soap that did not go through saponification. Increasing the amount of free-floating oils will slow down trace, but it also leads to a softer bar of soap that is more likely to develop DOS. In our experience, a superfat of 5 percent produces a balanced bar that behaves well.